On the surface the G7 Summit hosted by Japan in Hiroshima this month was a big success for Japan and for the G7, particularly in focusing attention on Russia`s invasion of Ukraine and strengthening G7 solidarity towards China.

But the success of the meeting masks the reality of an increasingly complex multipolar world in which the G7`s aspiration to global leadership is hotly challenged, not just by China and Russia but by the so-called Global South.

Japanese Prime Minister Kishida made a big effort ahead of the Summit to position Japan as a `bridge` to the Global South.

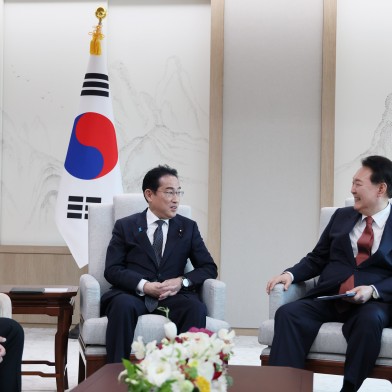

He travelled around Africa just before the event, and invited eight representative leaders from around the world: India (in its own right but also as President of the G20), Indonesia (similarly as Chair of ASEAN), South Korea, Brazil, Vietnam, Australia, the Comoros Islands, the Cook Islands and – the coup for Kishida – President Zelenskyy of Ukraine as a special guest.

In all, he secured the participation of leaders of 12 of the world`s top 16 economies (plus the EU), representing more than half of global GDP. China and Russia were of course the standout non-attendees.

Zelenskyy took the headlines with his last-minute appearance, reinforcing the perception of much of the world uniting in condemnation of Russia.

But a bit of digging behind the TV images casts doubt on how successful the G7 was in building ties with the Global South.

India`s Prime Minister Modi said he took the opportunity to “forcefully” raise the concerns of the Global South.

From Hiroshima he flew to Port Moresby for a gathering of Pacific leaders, including Prime Minister Hipkins. PNG Prime Minister Marape rolled out the red carpet, making an exception to a local rule of not welcoming visitors after sunset, and praised India as the “leader of the third world”.

For his part, Indonesia`s leader Joko Widodo returned from Hiroshima to immediately welcome Iran`s President Ebrahim Raisi to Jakarta.

Zelenskyy and President Lula of Brazil failed to hold a bilateral meeting at all in Hiroshima, exchanging barbs about who was responsible.

The enhanced confidence of Global South leaders reflects the long-term decline in the G7`s weight within the world economy - from 44 to 30 percent of global GDP between 2000 and 2023. China`s share has risen from 7 to 19 percent in the same period.

India is likely to overtake Japan and Germany as the world`s number three economy shortly.

Meanwhile the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) are holding their own summits: Foreign Ministers will meet in Cape Town this week, and leaders in August. On their agenda is enlargement: South Africa says more than 20 countries want to join.

The days of the G7 feeling in control of the world agenda are long gone.

Leaders such as Modi and Lula made clear they were meeting their G7 counterparts as peers not seniors. While listening to, and sometimes agreeing with G7 lines, they emphasized their policies were based on their own interests - not those of the G7.

Ukraine President Zelenskyy meets Indian leader Narendra Modi on the sidelines of the G7 meeting.

Brazil`s President Lula reportedly refused to stand like everyone else when President Biden entered the room – noting pointedly that no one had stood up for him when he entered.

G7-led sanctions against Russia, while maintaining pressure on Putin, are so far not delivering the knock-out blow their advocates hoped for, due largely to lack of support from the Global South.

Lula has condemned Russia`s invasion and recognized that Ukraine has the right to defend itself, but has criticized the US for insisting on unilateral Russian surrender rather than peace.

Modi has expressed clear concerns about China – hence India`s membership of the Quad – but has remained firmly neutral on Russia`s invasion of Ukraine.

The South`s position is not that Russia is right, but that this is a fight they do not wish to get involved in – just as the West has chosen not to intervene in many conflicts in other parts of the world.

As the G7 is finding, a multipolar world is likely to be a more complex one, and not necessarily more stable, more equal or more peaceful.

Indian and Chinese troops have fought across their border several times in the last couple of years.

Along with the G7, US-led multilateral institutions like the WTO, the World Bank and the IMF are also seeing their influence decline, largely due to their failure to share governance proportionately with rising powers, particularly China.

Not surprisingly, alternatives have emerged, such as the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the BRICs` New Investment Bank.

In this looser environment of weakened multinational rules and institutions, countries are looking to band together on particular issues where they see shared interests, not necessarily on the basis of traditional friendships or alliances.

The Quad (India, Australia, Japan, US) is one such example.

New Zealand did not attend the Hiroshima Summit – but two of its close friends did. While both largely share New Zealand`s worldview, there are important differences.

Prime Minister Albanese was there representing Australia, which by some measures is now one of the world`s top dozen economies.

Australia is a key supporter of the Quad, and a member of AUKUS. New Zealand has shown no interest in the Quad, and has rejected membership of the nuclear submarine component of AUKUS, though it is considering whether to participate in the non-nuclear `Pillar 2`.

Prime Minister Mark Brown of the Cook Islands was there in his capacity as Chair of the Pacific Islands Forum.

Brown`s invitation to the Summit indicates that smaller countries have scope to exercise leverage through like-minded groups – just as the big ones do.

Since New Zealand is a member of the Forum, this may be the first time in history that the Cook Islands, for a long period a dependency of New Zealand, instead represented New Zealand at a major international gathering.

Much of what Brown had to say – about climate change, economic development and the risks of militarization in the Pacific – could have come from the mouths of New Zealand ministers.

But his line that “the Pacific has always had a `friend to all and enemy to none` existence” is not one that New Zealand ministers would use or feel comfortable with.

Papua New Guinea`s Marape, who hosted PM Hipkins along with India`s Modi in Port Moresby right after the G7 Summit, has used identical words, including when welcoming China`s Special Envoy to PNG in March.

New Zealand policy, under governments of both left and right, has been to differentiate its friendships (and enmities) on the basis of national interests and values.

This is a small and manageable nuance, but it illustrates how New Zealand too is facing new challenges in navigating a looser and more competitive multipolar world.

+ The opinions expressed are those of the author +

Asia Media Centre